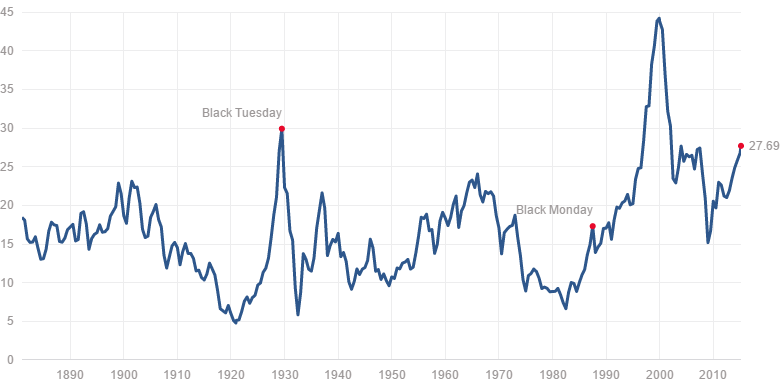

A lot of investors are looking at the CAPE or historical P/E ratios and scratching their heads. They’re wondering when the dreaded reversion to mean will happen. Because it always happens, right? Well, not necessarily. The CAPE has been rising in a long-term trend since the early 1980’s. There have been ups and downs, for sure, but still it seems that the taming of inflation and the enforcement of macroeconomic stability by the Fed has continuously improved stock market returns. So there’s an upward trend in the CAPE. Sometimes the market crashes, but it crashes to a higher level than previous rather than reverting to the mean.

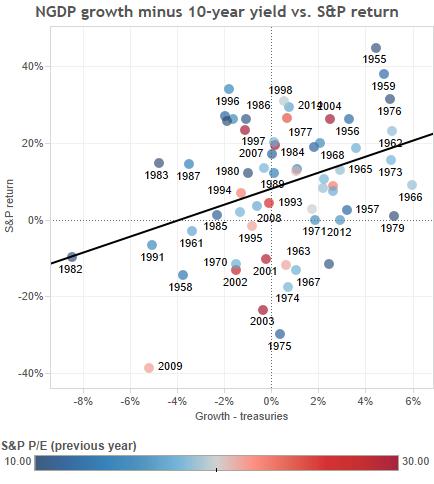

As a value investor, I love a good P/E ratio, but if you look at P/E vs. S&P returns, the P/E ratio does not predict next year’s returns very well. This is true even when you remove years where NGDP growth was under 2%, and other outliers. The relationship looks negative (ie. lower P/E correlates to higher returns), but there’s no statistical significance.

What correlates better to market returns? Monetary policy. But how do you tell when monetary policy is loose vs. tight? Almost everyone makes the mistake of assuming that low interest rates = easy money. This is actually the opposite of what happened in most cases. In the late 1970’s when inflation was roaring, interest rates were quite high. Compare that to the 1930’s or post-2008 when conditions were depressed, and interest rates were very low. Let’s look at the trend of nominal GDP growth, 10-year treasury yields and the difference between the two.

The higher NGDP growth is over 10-year treasuries, the “looser” policy is. Policy seems loose from the mid-1950’s until 1980, when interest rates spiked and inflation started to drop. Indeed since 1980 policy has been rather tight as NGDP growth has compressed. The only times interest rates fell significantly below NGDP are 1997-2000, 2004-2006 and since 2011. Funny enough, those three periods correspond to strong markets. When the gray line crosses below 0% (policy tightens), there’s a crash. If we plot the difference between NGDP growth and 10-year treasuries vs. S&P 500 returns, what do we get?

We get a correlation that is significant, and the relationship is more model-able at a 12% r-squared. Granted, this isn’t a perfect relationship, but it’s better than previous year P/E ratio.

Will the Fed leave well enough alone this time?

Today’s Fed seems smart enough to leave this market alone because there’s still an output hole to fill from the last contraction in 2008. You can see that by looking at this NGDP trend graph. Therefore, the Fed can leave interest rates lower while pumping up NGDP for a while longer, with strongly beneficial affects for the market.

But there’s still a danger that the Fed will tighten prematurely, which brings me back to the title of this article. To illustrate, here are a few quotes from monetary luminary Milton Friedman to chew on, as presented by the Cato Institute. They show us that 1) the Federal Reserve has a habit of going off the rails at the exact wrong moment and 2) this has had dire consequences for markets.

“We don’t need a Fed. I have, for many years, been in favor of replacing the Fed with a computer.”

“The Fed has had very few periods of relatively good performance. For most of its history, it’s been a loose cannon on the deck, and not a source of stability.”

“I do not believe the Fed ought to let its monetary policy be determined by the stock market. The Fed ought to devote its attention solely to keeping a relatively stable price level of goods and services.” He points to the bull markets in 1920s America and 1980s Japan. “Both of those were brought to an end by monetary policies adopted to bring them to an end.”

In 1928, the Fed tightened monetary policy “because of its concern with the stock market boom…If there had been no Fed, there would have been no Great Depression.” Early this decade, the Bank of Japan similarly slammed on the brakes. Japan skidded into a ditch from which it is emerging only now. “In both cases,” he says, “the central banks should not have been paying any attention to the stock market, but should have been concentrating on the price level in general.”

What would replacing the Federal Reserve with a computer look like? Instead of oracle-like, wizened old men (and women) giving us monetary policy from above, a computer could focus on a set of metrics without the psychological limitations of human beings. For example, when nominal GDP tanked in 2008-2009, the Federal Reserve, worried about perceptions, only hesitantly stepped in with greater amounts of QE to boost inflation expectations. Not high enough, it turns out, as it had to engage in two subsequent bouts of QE. Those successive rounds of QE are NOT inflationary, but rather they are a sign of the failure of the Fed to create inflation. You can’t blame Bernanke and Yellen too much, because Europe has seen demand collapse and stay collapsed. By taking even less action, the ECB ensured economic stagnation, high unemployment and social unrest. At least the Fed didn’t do nothing.

A computer, on the other hand, could automatically increase / decrease the supply of money depending on an all-encompassing macro-variable (like NGDP). For more on NGDP targeting, read Scott Sumner’s excellent blog.

Therefore, our investment returns are beholden to a centralized group of government workers who hold the reins of aggregate demand in their hands. They in turn may bow to various political pressures to abandon allegedly dangerous, easy money because of the collective misconception that lower rates = easy money.

I’m an optimist, and I think Yellen will do the right thing by holding rates at zero and waiting for stronger growth before tightening. But lately I see interest rates creeping up and NGDP growth slipping. If it happens too much, investors will be in great danger.

Leave a Reply