I’ve been thinking a lot about how economics resembles a biological system. In biology, introduce a new species into an environment and the other organisms must adjust to it. I touched on this in my post on how monetary policy is like the movie Speed. The speed of the bus stays the same, everyone else better get out of the way.

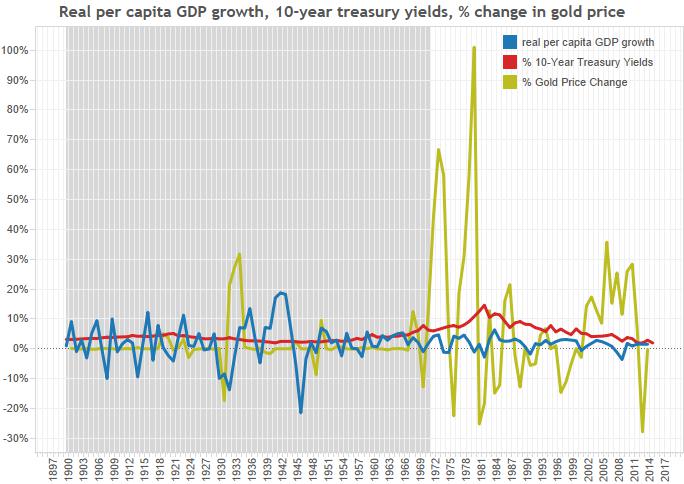

Below is a graph looking at three variables since 1900: real per capita GDP growth, 10-year treasury yields and the % change in the price of gold.

With three time series, we get three stories:

- Treasury yields don’t move around that much. They appear to drift higher in times of inflation, lower in times of depression. Since we think of interest rates as being the main tool of monetary policy, I suppose I’d expect more volatility in rates. This isn’t the case.

- The price of gold moves around a lot after we went off the gold standard. Of course this is expected as we stopped targeting the price of gold.

- Real per capita GDP moves quite violently before we went off the gold standard, more stably during the Bretton Woods system and after the US went off gold in 1971.

So what’s going on? It seems that interest rates don’t really take the brunt of adjustment in the US. Instead that adjustment comes through changes in real & nominal incomes. Before leaving the gold standard, economic imbalances were resolved almost completely through adjustments in nominal incomes, which then had effects on the volatility of real incomes as well. After adjusting and then leaving the gold standard, we moved volatility from the real economy to prices of commodities.

And that’s the right thing to do. After all, we all trade our labor for goods and services. It’s anachronistic to tie the value of our labor to the quantity of a pretty, yellow metal. Perhaps the stability of the 1950’s and 1960’s proves that a gold standard can coexist with stable incomes. If the central bank is willing to enforce income stability through reserve ratios or threats to alter the price of gold, then there need not be a problem. But if the goal of policy is stable (slowly growing) incomes, then why not just target that variable instead?

If history since the gold standard has proven anything, it’s that the Fed can cause lots of inflation (1970’s), can tame that inflation (early 1980’s) and can push inflation into an under-2% straight jacket (2008 until now). This is all with paper money. By focusing on 0%-2% inflation, the Fed is refusing to countenance an adjustment to higher debts through higher nominal incomes. Instead they forced the massive debt buildup before 2008 to resolve itself through defaults and crisis. Of course they thought better and began firing up the printing press afterwards. But the lack of confidence in the Fed to hit above-2% inflation (its inflation target seems more like 0%-2%) makes future adjustments to higher debt that much scarier.

To enforce a stable price of gold, the US tolerated large swings in nominal (and real) incomes. Since the 1960’s, the Fed has allowed lots of volatility in gold prices to preserve ever-growing incomes. Now volatility comes when we collectively lose confidence in the Fed to keep to its target. We lost confidence in the 1970’s (the Fed wasn’t able to control inflation), and we lost confidence in 2008 (the Fed wasn’t able to keep nominal income growth stable).

Whatever the Fed targets, there will be volatility elsewhere. We just need to make sure that the target is clear, and that it does the least amount of harm to the most number of people.

Leave a Reply