We’re hearing more about inequality, even from perennial Republican candidate for President Mitt Romney. Liberal economists like Thomas Piketty and Paul Krugman bemoan inequality in America. Some studies have even suggested that the liberation of women has contributed to the problem (educated working women marry educated working men, giving them a larger share of national income).

One of my favorite bloggers Scott Sumner, who has a lot to say on the causes of the financial crisis (tight monetary policy), doesn’t think inequality is a problem. Yet it feels like his solution (targeting nominal GDP) would certainly affect it.

Compared to current, tight monetary policy, NGDP targeting would create more inflation. Higher demand would push up prices, expectations of future growth would jump, and people would hoard less cash. But who’s hoarding all this cash? It’s the rich and big businesses with bloated cash piles, fearing the next liquidity crisis. Instead of investing in phantom demand, corporations are buying back shares. Increasing demand expectations would increase the velocity of money, thereby raising incomes and helping us all meet those long-term obligations (ie. mortgages) we took out before 2008.

Below is a chart looking at 10-year treasury yields vs. the share of income going to the top 1% since 1951. There appears to be a correlation in that ever-rising interest rates (which roughly equates to rising expectations of inflation) pushed down inequality. When interest rates started to tumble after Volker broke the back of inflation, inequality began to rise, shooting up between 1986 and 1988 (marked).

How do the two variables (yields vs. inequality) relate? It appears from the chart below that inequality is indeed negatively correlated to 10-year yields. The lower the yields, the higher the incomes of the top 1%. Before 1986 though, this relationship was more muted. Afterwards, it became more pronounced.

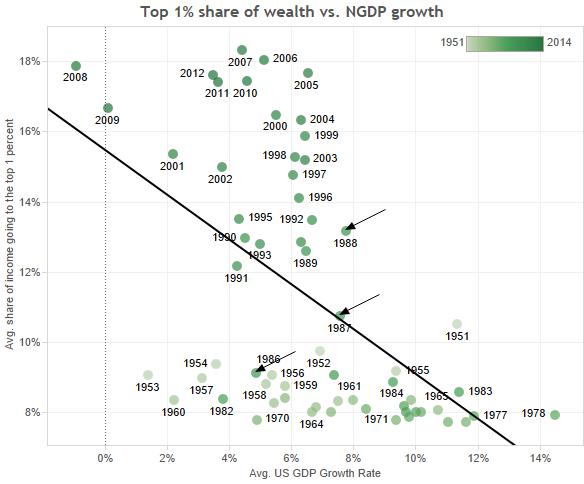

A similar graph below shows the correlation between Sumner’s favorite variable (NGDP) and inequality. Again the relationship is unmistakable. Again, the shift to a stronger relationship post-1986 appears.

A lot of variables were changing in the 1980’s. Reagan was enacting supply-side tax reform while moving against unions. Monetary policy became very tight to break inflation, then continued compressing inflation expectations downwards to this day. Third-world countries began competing for cheap labor with less-skilled American workers. Stock markets (on the back of lower interest rates) rose strongly. Any of these could be pivotal in causing more inequality.

But getting back to monetary policy, aggregate demand affects business investment. Inflation affects the timing of consumption. If aggregate demand and inflation are being squeezed by tighter and tighter monetary policy (as they have been since the early 1980’s), you’ll get a lower velocity of money and more cash hording by businesses and individuals.

For a very simple view of our economy, think of it as a poker game. You go to the table with your chips. Some win and some lose. In order to keep playing, eventually you’ll need more chips. An ultra-loose monetary policy floods the game with so many chips, that winning no longer becomes important. An ultra-tight policy denies new chips to the losers, effectively shutting them out of the game. A just-right policy will ease more chips into the game so that losers can keep coming back to the table, and winners need to keep winning to stay on top.

In 2008, it’s almost as if the winners took all the chips and left the table. They need a reason for a new game to give the rest of us more chances at winning. The new game is aggregate demand. That’s what causes investment opportunities, and it’s what gives the rich more reasons to spend (and workers a chance to make more income).

Is this redistribution of wealth? Yes, but it’s an efficient redistribution of wealth. The other way to reset the game is for a depression to destroy the winners’ chip (ie. securities) values anyway. Deflation and liquidation makes everyone a loser at a lower level of wealth. But that seems like an awful lot of trouble. If the central bank can simply force our expectations of aggregate demand higher at a constant level every year, businesses will have investment opportunities, savers will have normal interest rates and workers will be able to match their long-term debt with their expectations of future wage increases. In other words, everyone wins.

Leave a Reply